Learning about Psychological Safety at the Recurse Center

Oct 19th, 2021

Last summer, I took a 6-week sabbatical from my job to attend a virtual “programmers retreat” at the Recurse Center. I thought I’d write up some notes on the experience, with a particular lens towards what makes an environment suited towards learning, innovation, and personal growth.

Some context: I’m currently working as a software engineer at Mozilla, building out our data pipeline and analysis tooling. I’ve been at my current position for more than 10 years (my “anniversary” actually passed while I was out). I started out as a senior engineer in 2011, and was promoted to staff engineer in 2016. In tech-land, this is a really long tenure at a company. I felt like it was time to take a break from my day-to-day, explore some new ideas and concepts, and hopefully expose myself to a broader group of people in my field.

My original thinking was that I would mostly be spending this time building out an interactive computation environment I’ve been working on called Irydium. And I did quite a bit of that. However, I think the main thing I took away from this experience was some insight on what makes a remote environment for knowledge work really “click”. In particular, what makes somewhere feel psychologically safe, and how this feeling allows us to innovate and do our best work.

While the Recurse Center obviously has different goals than an organization that builds and delivers consumer software, I do think there are some things that it does that could be applied to Mozilla (and, likely, many other tech workplaces).

What is the Recurse Center?

Most succinctly, the Recurse Center is a “writer’s retreat for programmers”. It tries to provide an environment conducive to learning and creativity, an opportunity to refine your craft and learn new things, both from the act of programming itself and from interactions with the other like-minded people attending. The Recurse Center admits a wide variety of people, from those who have only been through a coding bootcamp to those who have been in the industry many years, like myself. The main admission criteria, from what I gather, are curiosity and friendliness.

Once admitted, you do a “batch”— either a mini (1 week), half-batch (6 weeks), or a full batch (12 weeks). I did a half-batch.

How does it work (during a global pandemic)?

The Recurse experience used to be entirely in-person, in a space in New York City - if you wanted to go, you needed to move there at least temporarily. Obviously that’s out the window during a Global Pandemic, and all activities are currently happening online. This was actually pretty ideal for me at this point in my life, as it allowed me to participate entirely remotely from my home in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada (near Toronto).

There’s a few elements that make “Virtual RC” tick:

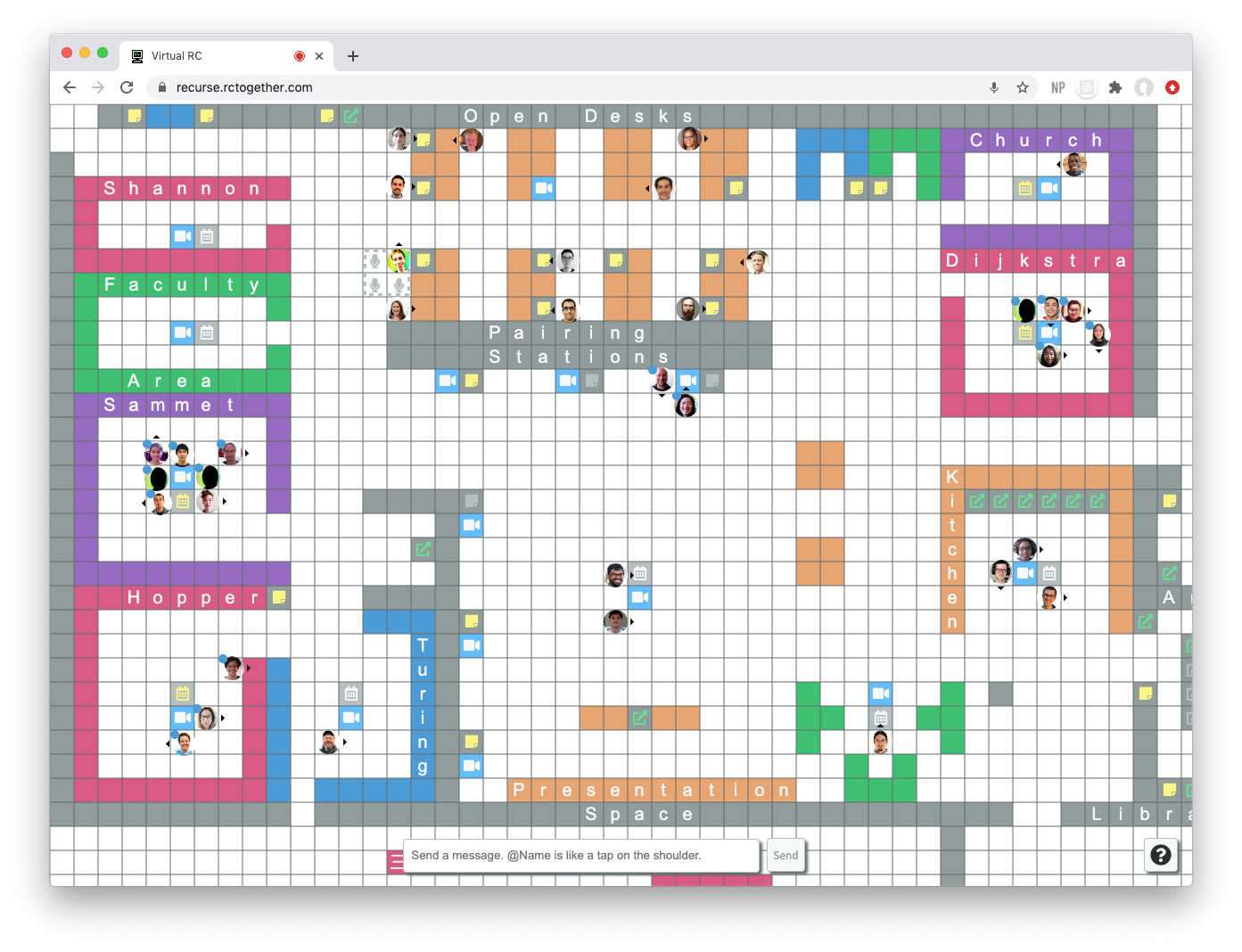

- A virtual space (pictured below) where you can see other people in your cohort. This is particularly useful when you want to jump into a conference room.

- A shared “calendar” where people can schedule events, either adhoc (e.g. a one off social event, discussing a paper) or on a regular basis (e.g. a reading group)

- A zulip chat server (which is a bit like Slack) for adhoc conversation with people in your cohort and alumni. There are multiple channels, covering a broad spectrum of interests.

Why does it work?

So far, what I’ve described probably sounds a lot like any remote tech workplace during the pandemic… and it sort of is! In some ways, my schedule and life while at Recurse didn’t feel all that different from my normal day-to-day. Wake up in the morning, drink coffee, meditate, work for roughly 8 hours, done. Qualitatively, however, my experience at Recurse felt unusually productive, and I learned a lot more than I expected to: not just the core stuff related to Irydium, but also unexpected new concepts like CRDTs, product design, and even how visual studio code syntax highlighting works.

What made the difference? Certainly, not having the normal pressures of a workplace helps - but I think there’s more to it than that. The way RC is constructed reinforces a sense of psychological safety which I think is key to learning and growth.

What is psychological safety and why should I care?

Psychological safety is a bit of a hot topic these days and there’s a lot of discussion about in management circles. I think it comes down to a feeling that you can take risks and “put yourself out there” without fear that you’ll be ignored, attacked, or ridiculed.

Why is this important? I would argue, because knowledge work is about building understanding — going from a place of not understanding to understanding. If you’re working on anything at all innovative, there is always an element of the unknown. In my experience, there is virtually always a sense of discomfort and uncertainty that goes along with that. This goes double when you’re working around and with people that you don’t know terribly well (and who might have far more experience than you). Are they going to make fun of you for not knowing a basic concept or for expressing an idea that’s “so wrong I don’t even know where to begin”? Or, just as bad, will you not get any feedback on your work at all?

In reality, except in truly toxic environments, you’ll rarely encounter outright abusive behaviour. But the isolation of remote work can breed similar feelings of disquiet and discomfort over time. My sense, after a year of working “hardcore” remote in COVID times, is that our normal workplace rituals of meetings, “stand ups”, and discussions over Slack don’t provide enough space for a meaningful sense of psychological safety to develop. They’re good enough for measuring progress towards agreed-upon goals but a true sense of belonging depends on less tightly scripted interactions among peers.

How the Recurse environment creates psychological safety

But the environment I described above isn’t that different from a workplace, is it? Speaking from my own experience, my coworkers at Mozilla are all pretty nice people. There’s also many channels for informal discussion at Mozilla, and of course direct messaging is always available (via Slack or Matrix). And yet, I still feel there is a pretty large gap between the two experiences. So what makes the difference? I’d say there were three important aspects of Recurse that really helped here: social rules, gentle prompts, and a closed space.

Social rules

There’s been a lot of discussion about community participation guidelines and standards of behaviour in workplaces. In general, these types of policies target really egregious behaviour like harassment: this is a pretty low bar. They aren’t, in my experience, sufficient to actually create an environment that actually feels safe.

The Recurse Center goes over and above a basic code of conduct, with four simple social rules:

- No well-actually’s: corrections that aren’t relevant to the point someone was trying to make (this is probably the rule we’re most heavily conditioned to break).

- No feigned surprise: acting surprised when someone doesn’t know something.

- No backseat driving: lobbing advice from across the room (or across the online chat) without really joining or engaging in a conversation.

- No subtle -isms: subtle expressions of racism, sexism, ageism, homophobia, transphobia and other kinds of bias and prejudice.

These rules aren’t “commandments” and you’re not meant to feel shame for violating them. The important thing is that by being there, the rules create an environment conducive to learning and growth. You can be reasonably confident that you can bring up a question or discussion point (or respond to one) and it won’t lead to a bad outcome. For example, you can expect not to be made fun of for asking what a UNIX socket is (and if you are, you can tell the person doing so to stop). Rather than there being an unspoken rule that everyone should already know everything about what they are trying to do, there is a spoken rule that states it’s expected that they don’t.

Working on Irydium, there’s an infinite number of ways I can feel incompetent: this is a requirement when engaging with concepts that I still don’t feel completely comfortable with: parsers, compilers, WebAssembly… the list goes on. Knowing that I could talk about what I’m working on (or something I’m interested in) and that the responses I got would be constructive and directed to the project, not the person made all the difference.1

Gentle prompts

The thing I loved the most about Recurse were the gentle prompts to engage with other people, talk about your work, and get help. A few that I really enjoyed during my time there:

- The “checkins” channel. People would post what’s going on with their time at RC, their challenges, their struggles. Often there would be little snippits about people’s lives in there, which built to a feeling of community.

- Hack & Tell: A weekly event where a group of us would get together in a Zoom room, talk about working on or building something, then rejoin the chat an hour later to show off what we accomplished.

- Coffee Chats: A “coffee chat” bot at RC would pair you with other people in your batch (or alumni) on a cadence of your choosing. I met so many great people this way!

- Weekly Presentations: At the end of each week, people would sign up to share something that they were working on our learned.

… and I could go on. What’s important are not the specific activities, but their end effect of building connectedness, creating opportunities for serendipitous collaboration and interaction (more than one discussion group came out of someone’s checkin post on Zulip) and generally creating an environment well-suited to learning.

A (semi) closed space

One of the things that makes the gentle prompts above “work” is that you have some idea of who you’re going to be interacting with. Having some predictability about who’s going to see what you post and engage with you (that they were vetted by RC’s interview process and are committed to the above-mentioned social rules) gives you some confidence to be vulnerable and share things that you might be reluctant to otherwise.

Those who have known me for a while will probably see the above as being a bit of departure from what I normally preach: throughout my tenure at Mozilla, I’ve constantly pushed the people I’ve worked with to do more work in public. In the case of a product like Firefox, which touches so many people, I think open and transparent practices are absolutely essential to building trust, creating opportunity, and ensuring that our software reflects a diversity of views. I applied the same philosophy to Irydium’s development while I was at the Recurse Center: I set up a public Matrix channel to discuss the project, published all my work on GitHub, and was quite chatty about what I was working on, both in this blog and on Twitter.

The key, I think, is being deliberate about what approach you take when: there is a place for both public and private conversations about what we work on. I’m strongly in favour of open design documents, community calls, public bug trackers and open source in general. But I think it’s also pretty ok to have smaller spaces for learning, personal development, and question asking. I know I strongly appreciated having a smaller group of people that I could talk to about ideas that were not yet fully formed: you can always bring them out into the open later. The psychological risk of working in public can be mitigated by the psychological safety that can be developed within an intentional community.

Bringing it back

Returning to my job, I wondered if it might be possible to bring some of what I described above back to Mozilla? Obviously not everything would be directly transferable: Mozilla has its own mission and goals, and there are pressures that exist in a workplace that do not exist in an environment purely directed at learning. Still, I suspected that there was something we could do here. And that it would be worth doing, not just to improve the felt experience of the people here (though that would be reason enough) but also to get more feedback on our work and create more opportunities for collaboration and innovation.

I felt like trying to do something inside our particular organization (Data Engineering and Data Science) would be the most tractable initial step. I talked a bit about my experience with Will Kahn-Green (who has been at Mozilla around the same length of time as I have) and we came up with what we called the “Data Neighbourhood” project: a set of grassroots micro-initiatives to increase our connectedness as a group. As an organization directed primarily at serving other parts of Mozilla, most of our team’s communication is directed outward. It’s often hard to know what everyone else is up to, where they’re struggling, and how we could help each other out. Attacking that problem directly seemed like the best place to start.

The first experiment we tried was a “data checkins” channel on Slack, a place for people to talk informally about their work (or life!). I explicitly set it up with a similar set of social rules as outlined above and tried to emphasize that it was a place to talk about how things are going, rather than a place to report status to your manager. After a somewhat slow start (the initial posts were from Will, myself, and a few other people from Data Engineering who had been around for a long time) we’re beginning to see engagement from others, including some newer people I hadn’t interacted with much before. There’s also been a few useful threads of conversations across different sub-teams (for example, a discussion on how we identify distinct versions of Firefox for iOS) that likely would not have happened without the channel.

Since then, others have tried a few other things in the same vein (an adhoc coffee chat pairing bot, a “writing help” channel) and there are some signs of success. There’s clearly an appetite for new and better ways for us to relate to each other about the work we’re doing, and I’m excited to see how these ideas evolve over time.

I suspect there are limits to how psychologically safe a workplace can ever feel (and some of that is probably outside of any individual’s control). There are dynamics in a workplace which make applying some of Recurse’s practices difficult. In particular, a posture of “not knowing things is o.k.” may not apply perfectly to a workplace where people are hired (and promoted) based on perceived competence and expertise. Still, I think it’s worth investigating what might be possible within the constraints of the system we’re in. There are big potential benefits, for our creative output and our well-being.

Many thanks to Jenny Zhang, Kathleen Beckett, Joe Trellick, Taylor Phebillo and Vaibhav Sagar, and Will Kahn-Greene for reviewing earlier drafts of this post

-

This is generally considered best practice inside workplaces as well. For example, see Google’s guide on how to write code review comments. ↩